ASEAN countries are scrambling to align data protection laws From comprehensive policies to emerging frameworks, how are they keeping up with global standards like the GDPR?

In an increasingly interconnected world, the significance of data protection has risen dramatically, particularly within the dynamic landscape of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As digital technologies continue to reshape economies, societies, and personal interactions, the need for robust data protection frameworks becomes paramount. With varying degrees of legislation across member states, from comprehensive laws to emerging frameworks, the region faces a unique challenge: harmonizing data protection standards to safeguard the rights of individuals while fostering innovation and economic growth.

This article explores the current state of data protection laws in ASEAN countries, examining recent developments, ongoing reforms, and the pressing need for updates. By assessing the effectiveness of existing regulations, addressing the gaps and challenges faced by each nation, and considering the impact of global standards such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), we can better understand the path forward for a unified approach to data protection in the region. Ultimately, as ASEAN countries strive to balance privacy rights with the demands of a digital economy, the evolution of data protection laws will play a critical role in shaping the future of data governance in Southeast Asia.

Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA)

Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (2020 Revised Edition), governed by the Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPC) under the Infocomm Media Development Authority, is a comprehensive framework for safeguarding personal data. Notably, the PDPA applies to any processing activity that occurs in Singapore—even if the organization has no physical presence in the country.

Key Provisions:

- Controller and Processor Distinction: The PDPA distinguishes between data controllers and processors, ensuring clarity in data management responsibilities.

- Sensitive Personal Data: While the PDPA doesn’t explicitly define sensitive data, it places significant emphasis on protecting data such as national identification numbers, with mandatory reporting required in case of a breach likely to cause significant harm.

- Lawful Bases for Processing: Data can be processed based on consent, legitimate interests, business improvement purposes, investigations, or as required by other written laws. This flexibility allows businesses to align with their operational needs while maintaining compliance.

- Security Requirements: Organizations must implement reasonable technical, administrative, and physical security measures to safeguard personal data.

Data Subject Rights are robust under the PDPA, including the right to withdraw consent, the right of access, the right to correction, and the upcoming right to data portability. These provisions empower individuals to maintain control over their personal information.

For organizations transferring data across borders, the PDPA offers several mechanisms to ensure compliance, with legally binding contracts being the most common method.

Additional Requirements:

- Data Protection Officer (DPO): Every organization, regardless of size, must appoint at least one DPO to oversee compliance with the PDPA.

- Breach Notification: In the event of a data breach, organizations must notify the PDPC within three calendar days and inform affected individuals without undue delay.

- Employment Context: The PDPA provides specific exceptions to consent requirements in employment contexts, where processing is necessary for evaluative purposes or the management/termination of an employment relationship.

- Minors: Parental or guardian consent is required when processing personal data of minors under the age of 13.

Direct Marketing rules are stringent. Clear, unambiguous opt-in consent is required for telemarketing activities (phone, SMS, fax) if the number is registered on Singapore’s Do Not Call Registry.

Notably, business contact information is excluded from the PDPA, ensuring businesses can operate efficiently without overextending privacy obligations.

Penalties for non-compliance can be significant, with fines reaching up to 10% of annual domestic turnover. Furthermore, individuals have a private right of action, although class actions are not permitted under the PDPA.

Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act 2019 (PDPA)

Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act 2019 (PDPA) sets forth a robust framework for safeguarding personal data. The law is supervised by the Personal Data Protection Commission(PDPC) and applies to both domestic and international organizations processing the personal data of individuals in Thailand.

Key Provisions:

- Scope of Application: The PDPA applies to organizations located within Thailand and those outside of Thailand offering goods or services to data subjects in the country or monitoring their behavior. This wide scope ensures that data subjects’ rights are protected, regardless of where the data processing occurs.

- Controller and Processor Distinction: The PDPA draws a clear distinction between data controllers and processors, ensuring transparency and accountability in the handling of personal data.

- Sensitive Personal Data: Special protections apply to sensitive data, including information on race, ethnicity, political opinions, religious beliefs, trade union membership, genetic and biometric data, health, sex life or orientation, and criminal convictions.

- Lawful Bases for Processing: Data processing under the PDPA must be based on consent or specific lawful bases such as contract performance, legal obligations, protection of vital interests, public interest, legitimate interests of the controller or third party, or preparation of historical documents for research or public purposes.

Data Security and Rights:

- Security Measures: Organizations are required to implement appropriate technical, administrative, and physical security measures to protect personal data from unauthorized access, loss, or disclosure.

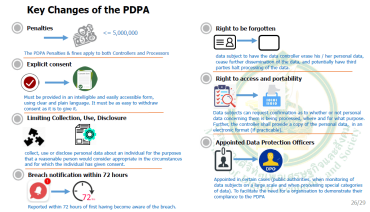

- Data Subject Rights: Individuals are empowered under the PDPA with extensive rights, including the right to withdraw consent, right of access, right to rectification, right to erasure, right to restrict or object to processing, right to data portability, and the right to lodge a complaint with the PDPC.

Cross-Border Data Transfers: Transfers of personal data outside Thailand are only allowed to jurisdictions on a PDPC-approved whitelist or under binding corporate rules, standard contractual clauses, lawful processing bases, or for the exercise or defense of legal claims.

Additional Requirements:

- Data Protection Officer (DPO): Organizations engaged in regular monitoring of large volumes of personal data, or whose core activity involves the processing of sensitive data, must appoint a Data Protection Officer.

- Breach Notification: In the event of a data breach, organizations must notify the PDPC within 72 hours of discovery. Additionally, if the breach poses a high risk to individuals’ rights, those affected must also be notified without undue delay.

Employment Context: The PDPA does not set out any special rules for employee data. Therefore, data subjects in employment contexts are treated similarly to those outside of such contexts.

Minors: The consent of a parent or legal guardian is required for processing the personal data of minors under the age of 10. For those aged 10 to 20 who are unmarried or not legally sui iuris, consent is still required.

Direct Marketing: Direct marketing requires prior opt-in consent, whether conducted through online channels, email, telephone, SMS, or post.

Penalties and Enforcement:

- Fines and Imprisonment: Violations of the PDPA can lead to fines of up to THB 5,000,000 (approx. USD 144,000) for civil infractions. Criminal violations carry fines of up to THB 1,000,000 (approx. USD 28,700) and/or imprisonment for up to one year.

- Private Right of Action: Individuals also have the right to seek punitive damages up to twice the actual compensation.

Vietnam’s Personal Data Protection Decree (PDPD)

Vietnam is strengthening its commitment to personal data protection, issuing a Draft Law on Data Protection built upon the foundation laid by Decree 13 on Personal Data Protection (PDPD), which came into effect in July 2023. The Decree, enforced by the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), establishes a robust framework for protecting personal data within Vietnam. However, the evolving digital landscape demands a more comprehensive approach, leading to the Draft Law on Personal Data Protection, which is expected to come into force from January 1, 2026.

Key Highlights of Decree 13:

- Broad Scope of Application: The Decree applies to all organizations processing personal data in Vietnam or handling the data of individuals located in Vietnam, regardless of the organization’s physical location. This underscores the extraterritorial reach of the Vietnamese data protection regime.

- Consent as the Cornerstone: Organizations must obtain informed and unambiguous consent from data subjects before processing their personal data.

- Emphasis on Data Subject Rights: Decree 13 empowers data subjects with a comprehensive set of rights, including the right to access, rectification, erasure, and objection to processing, aligning with global data protection principles.

Draft Law: A Leap Towards a More Robust Framework

While Decree 13 provides a solid foundation, the Draft Law significantly expands upon it. Some notable aspects include:

- Elevating Data Protection to “Original Law”: The Draft Law serves as a primary legal framework, solidifying and clarifying various aspects of Decree 13. It aims to unify legal terminology related to personal data protection, fostering consistency within the Vietnamese legal system.

- Aligning with International Best Practices: Recognizing the global nature of data flows, the Draft Law draws inspiration from international regulations, including the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), ensuring compatibility with global standards.

- Introducing DPOs and a Credit Rating System: The Draft Law mandates the appointment of Data Protection Officers (DPOs) for organizations. Additionally, it establishes a credit rating system for personal data protection, adding a layer of accountability and promoting responsible data handling practices.

- Strengthening Cross-Border Data Transfer Mechanisms: The Draft Law establishes a more stringent process for cross-border data transfers, requiring organizations to complete and submit a Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA) Dossier to the MPS.

The Draft Law signals Vietnam’s commitment to staying at the forefront of personal data protection. By establishing a more comprehensive legal framework, fostering accountability, and aligning with international standards, Vietnam aims to create a secure and trustworthy digital environment for businesses and individuals alike.

Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act 2010

Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (PDPA) provides a solid regulatory framework for managing personal data. Overseen by the Personal Data Protection Department (PDPD) under the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia, the PDPA applies to any organization that processes personal data within or outside Malaysia, provided the goods or services are offered in Malaysia.

Core Highlights:

- Scope of Application: The PDPA applies to organizations both within Malaysia and those outside Malaysia offering services or goods to individuals located in the country.

- Controller/Processor Distinction: Yes, the PDPA distinguishes between data controllers and data processors, ensuring both have specific responsibilities in managing personal data.

Sensitive Personal Data:

The law covers various categories of sensitive data including:

- Political opinions

- Religious or philosophical beliefs

- Genetic data

- Biometric data

- Health data

- Criminal convictions

Lawful Bases for Processing:

Data processing under the PDPA must be based on:

- Consent of the data subject

- Performance of a contract

- Legal obligations

- Protection of vital interests

- Public functions conferred by law

- Administration of justice

Security Requirements:

Organizations must implement reasonable security measures, both technical and organizational, to ensure the protection of personal data.

Data Subject Rights:

Individuals are entitled to:

- Right to withdraw consent

- Right of access to personal data

- Right to rectification

- Right to object to processing

- Right to opt out of direct marketing communications

Cross-Border Transfers:

While a draft whitelist of approved countries for data transfers is under review, organizations must exercise caution when transferring data outside Malaysia.

Compliance Requirements:

Certain sectors, including banks, insurers, healthcare institutions, tour operators, higher education institutions, and utilities, are required to register under the Personal Data Protection (Class of Data Users) Order 2013.

No Breach Notification Requirement:

Unlike many data protection laws, the Malaysian PDPA does not currently mandate breach notification. However, organizations are still expected to maintain a high standard of data security.

Employment Context:

There are no special provisions regarding personal data in employment relationships. Employees have the same rights and protections as other data subjects.

Minors:

Data concerning minors under the age of 18 requires parental or legal guardian consent, ensuring that minors’ privacy is safeguarded.

Direct Marketing:

Organizations must obtain specific consent for direct marketing, including through online channels, email, telephone, SMS, and post. Notices and consents must be bilingual—in English and Bahasa Malaysia.

Penalties:

Organizations that fail to comply with the PDPA may face severe penalties, including:

- Fines of up to MYR300,000 (approx. US$65,000) and/or up to two years’ imprisonment for breaches.

- For failure to register with the PDPD, fines of up to MYR500,000 (approx. US$108,000) and/or three years’ imprisonment can be imposed.

Private Right of Action:

Data subjects have the right to seek redress for violations of the PDPA, ensuring that their privacy rights are enforceable in the courts.

Philippines Data Privacy Act 2012

The Data Privacy Act 2012 (DPA), overseen by the National Privacy Commission (NPC), establishes crucial protections for personal data in the Philippines.

Scope of Application:

Applies to organizations in the Philippines and those processing data of individuals in the Philippines, including foreign entities with relevant ties.

Controller/Processor Distinction:

Yes, the DPA distinguishes between data controllers and processors.

Sensitive Personal Data Includes:

- Race or ethnicity

- Political opinions

- Religious beliefs

- Health data

- Criminal convictions

Lawful Bases for Processing:

Requires a legitimate purpose and/or informed consent, with strict privacy notice requirements.

Security Requirements:

Organizations must implement reasonable security measures to protect personal data.

Data Subject Rights:

Rights include withdrawal of consent, access, rectification, erasure, objection to processing, data portability, and indemnity.

Cross-Border Transfers:

Requires approved contracts or rules to protect data being transferred outside the Philippines.

Data Protection Officer Requirement:

Organizations must appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO).

Breach Notification:

Organizations must notify the NPC and affected individuals within 72 hours of a breach involving sensitive personal data.

Penalties for Violations:

Fines range from 0.5% to 3% of annual gross income, with additional penalties for serious breaches.

Private Right of Action:

Individuals can seek damages for violations of the DPA.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat.

Indonesia Data Protection Law Overview

Law Name: Law No. 27 of 2022 Concerning Personal Data Protection Law

Supervisory Authority: Ministry of Communications and Informatics (interim).

Scope:

Covers processing with legal consequences in Indonesia or involving Indonesian citizens abroad.

Sensitive Data:

Includes health, biometric, genetic data, political views, and criminal records.

Lawful Bases for Processing:

- Explicit consent

- Contract performance

- Legal obligations

- Vital interests

- Public interest

- Legitimate interests

Security Requirements:

Implement technical and operational measures to secure personal data.

Data Subject Rights:

- Withdraw consent

- Access and rectify data

- Object to processing

- Request deletion and data portability

Cross-Border Transfers:

Allowed with equivalent protection, binding safeguards, or consent.

Data Protection Officer:

Required for certain processing activities.

Breach Notification:

Must notify authorities and affected individuals within three days.

Minors:

Parental consent required for those under 18.

Direct Marketing:

Opt-in consent needed.

Penalties:

Fines up to 2% of annual revenue.

Private Right of Action: Yes.

Cambodia Data Protection Law

Law on Cybercrime and the Personal Data Protection Law (PDP Law) effective 2023

Cambodia’s legal framework for data protection is still developing. Currently, there are no comprehensive laws defining “data controllers” or “data processors.” However, personal data is loosely defined under the E-Commerce Law as any information related to an individual, including names, biometric data, and identification numbers. The Sub-Decree No. 252 further outlines “personal identification data.”

There is no distinction between general and sensitive data, though medical, financial, and children’s data are considered sensitive in sectors like healthcare and banking.

Service providers must ensure data security and inform users about data usage under the E-Commerce Law. Data breaches can lead to imprisonment (1-2 years) and fines. Rights to data access, rectification, and opting out of marketing are protected, though erasure and portability rights are not explicitly mentioned.

Penalties for data breaches include both criminal and civil actions, with possible jail time and fines.

Brunei Darussalam Data Protection

Status: Draft Personal Data Protection Order.

Authority:

Brunei’s Authority for Info-Communications Technology Industry (AITI).

Overview:

AITI is developing a comprehensive Personal Data Protection law to regulate the collection, use, and disclosure of personal data by private entities.

Key Features:

- Recognizes individuals’ rights to protect personal data and outlines the responsibilities of private sector entities.

- Addresses consent requirements, purpose limitations, organizational obligations, data breach notifications, and data transfer provisions.

- No distinction between types of personal data; uniform protection measures required for all data.

Status:

Public consultation occurred in May 2021, with a response paper published in December 2021.

Myanmar Data Protection

Current Legislation:

- No specific data protection laws.

- Regulatory framework includes the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens (2017) and sector-specific legislation (e.g., Telecommunications Law 2013 and Financial Institutions Laws 2016).

Key Points:

- The Privacy Law applies only to Myanmar citizens and does not extend to non-citizens.

- Prohibits unauthorized activities by authorities affecting citizens’ privacy without presidential or governmental approval, such as:

- Spying or investigation.

- Acquiring personal communication data from telecom operators.

Consent:

- No explicit requirement for prior consent to process personal data, but consent is generally requested as a good practice aligned with international standards.

Challenges:

- Data privacy obligations are dispersed across various laws, focusing on confidentiality rather than dedicated protection.

- Lack of a specific data protection authority limits individuals’ knowledge of their privacy rights and options for redress.

Urgent Need:

- Increasing electronic transactions highlight the necessity for dedicated legislation addressing data protection issues.

Lao Data Protection

Law: Electronic Data Protection Act 2017

Regulator: Ministry of Post, Telecommunications and Communications

The Electronic Data Protection Act, effective since 2017, provides data protection for Lao citizens in the context of electronic information collection, access, use, and disclosure. It establishes key principles including consent, data retention, deletion practices, and data accuracy. The Act is supplemented by an implementation guide, offering examples of how organizations can comply with data protection procedures.

Next Steps for Businesses on Data Privacy in ASEAN

Stay Informed

- Data privacy regulations in ASEAN are not uniform, and countries are at different stages of development in terms of legal frameworks. For example, Thailand has enacted the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), while Singapore enforces its Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) with different nuances.

- Businesses should actively monitor regulatory updates, case law, and guidelines issued by data protection authorities in the countries they operate. Subscribing to newsletters, attending webinars, and engaging with legal advisors or privacy professionals can help businesses remain informed about the latest compliance requirements.

- Regularly training employees on data privacy rules is crucial to maintaining an informed and prepared workforce, especially as new rules emerge.

Ensure Compliance

- Obtaining Consent: One of the key principles of data privacy in ASEAN regulations is obtaining explicit consent from data subjects before collecting and processing their personal data. This may involve updating privacy policies, revising consent forms, and ensuring clear communication with customers regarding how their data will be used.

- Securing Data: Implementing stringent security measures is essential to prevent data breaches. Businesses must adopt encryption, access controls, and regular security audits to safeguard sensitive information. Incident response plans should also be developed and regularly tested.

- Appointing DPOs: Several ASEAN countries require businesses to appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO) responsible for overseeing data management practices and ensuring compliance with local laws. Even if not mandatory, having a dedicated DPO or team to handle privacy concerns can improve risk management and build trust with customers.

Manage Cross-border Data Transfers

- Transferring personal data across national borders can be complex due to varying data localization laws in ASEAN. For instance, Vietnam’s cybersecurity law mandates data localization, while other countries may have restrictions on exporting data unless certain safeguards (e.g., Standard Contractual Clauses, Binding Corporate Rules) are in place.

- Businesses need to evaluate how data flows within their organization, ensuring that any cross-border data transfers meet the legal requirements of both the exporting and receiving countries. This might involve updating data transfer agreements, conducting risk assessments, or implementing encryption and pseudonymization to protect data in transit.

- Participating in international certifications, such as the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system, can also be beneficial in managing compliance across multiple ASEAN markets.

By focusing on these areas, businesses operating in ASEAN can not only comply with current data privacy regulations but also position themselves for long-term success in a region that is increasingly prioritizing data protection and security.

Conclusion

Moving forward, ASEAN countries must prioritize collaboration and knowledge sharing to create a cohesive data protection strategy that respects individual rights while promoting economic growth and innovation. By learning from each other’s experiences and aligning with international standards, such as the GDPR, ASEAN can establish a strong foundation for data protection that meets the needs of its citizens and businesses alike.

In conclusion, the path towards effective data protection in ASEAN is not just a regulatory challenge; it is an opportunity to foster trust in digital ecosystems, protect personal privacy, and pave the way for a secure and sustainable digital future in the region. As member states navigate this complex landscape, the commitment to update and strengthen data protection laws will be essential in achieving these goals.

Have questions or need expert advice on compliance? Contact us today to ensure your business stays ahead!

- https://www.multilaw.com/Multilaw/Data_Protection_Laws_Guide/Data_Protection_Laws_Guide.aspx

- https://www.inhousecommunity.com/

- https://www.privacyworld.blog/privacy-asia-pacific/

- https://www.dataguidance.com/

- https://pdpathailand.com/pdpa/index_eng.html?srsltid=AfmBOoqi4Cs2gcGvc86JIG5ZesWDJ1QiYG3ir3BKF7SexxJuTIDFzd6x

- https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/overview-of-pdpa/the-legislation/personal-data-protection-act

- https://privacy.gov.ph/data-privacy-act/

- https://jdih.setkab.go.id/PUUdoc/176837/Salinan_UU_Nomor_27_Tahun_2022.pdf

- https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnam-law-on-personal-data-protection-latest-developments-and-insights.html/

- https://mohre.um.edu.my/img/files/Personal%20Data%20Protection%20(PDPA)%20Act%202010.pd

ไทย

ไทย 日本語

日本語 Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt ភាសាខ្មែរ

ភាសាខ្មែរ